“Power is in tearing human minds to pieces and putting them together again in new shapes of your own choosing.”

– George Orwell, 1984

Do you remember the first time you were introduced to queer theory?

For me, it was the word “genderfluid” at twelve or thirteen. The word started popping up in online spaces and by fourteen I was being told by friends, when I discussed my discomfort with nudity and my confused sexual identity, that I was “probably genderfluid”. Around that time I remember breaking down in tears in front of my computer, unable to understand why terminology that had been acceptable a few months ago was now heretical to even discuss. Perhaps it was about the infamous “trans*” argument, or perhaps it was about any number of other words and phrases that were at one point mandatory to use and are now considered to be on the same level as a transphobic slur.

Now, things are different. Online spaces and social media are still highly responsible for introducing pre-teenage children to gender identity and queer theory, offering a whole new language and several new guidelines on how one should identify based on one’s personality, history, and any number of other traits. There is also representation on television, like I Am Jazz, a reality series featuring a paediatric transitioner. Here in the UK, a NHS survey was issued to ten year old school children, asking them to define themselves as male or female and introducing them to the concept of being neither.

You’re probably thinking — so what? Arguing that children should be sheltered from LGBT identities is the oldest trick in the book. Conservatives have for years put forward the idea that children learning about homosexuality might somehow turn them gay, and being sceptical of how the concept of gender identity is introduced to children might seem to be a mirror of that. But that brings us back to the age-old question:

What makes someone trans?

And further, what makes some people trans, but not other people?

Is there any real criteria for being trans?

Does have someone have to reach a certain academic or spiritual understanding of gender before they can call themselves trans? Or is it a gene, or an inborn trait, like being gay, or being left handed? Or is just a word we use to define ourselves in relation to social roles, whether in support of them, or in protest?

Let me put it this way: if gender is a social construct, transgenderism must be a social construct too. If being transgender is a social construct, then it can’t be innate. If transgenderism isn’t innate, the narrative of being “born trans” falls apart, as does the idea that there are countless children sitting in classrooms who are inherently transgender and cisgender and that only these predetermined children would feel the need to further look into the new concepts they’ve been introduced to at school, online, or on television. The current narrative is like a time travel paradox: “if you’re trans now, you were always trans”. But what if that isn’t true?

More specifically, what if “being trans” is the answer we’re given for possessing any number of different traits, from being alienated from our own sex due to being gay or bisexual, feeling dissociated from our body after sexual abuse, or being vehemently disinterested in performing the roles our assigned gender is supposed to perform?

What if we’re drawn to this conclusion because being trans is, and always has been, marketed to us as something that makes people happy, “euphoric”, that being accepted as our chosen gender is blissful, and that there is surgery available to fix whatever we don’t like about our bodies? What if we’re drawn in by the idea that we can start over, and be anyone we want?

What if the narrative that there is no real criteria for being trans, other than “feeling trans” or some similarly vague emotion, means that there is potential for anyone, absolutely anyone, to find themselves identifying as transgender if the prospect is made to seem inviting enough?

And what evidence is there that introducing people to queer theory doesn’t lead to trans identification, not overnight, but through a series of stages, each with its own distinct methods of manipulation, taking a person through simply hearing a word they didn’t know to drastically altering their lives?

Step One

Introduction: The Language Puzzle

Let’s rewind.

I said that my first introduction to queer theory was the term “genderfluid”, but I’m sure for other people, it was something else. Maybe “nonbinary”, or something like “cisgender”. Maybe they were accused of transmisogyny after taking an insensitively worded sign to a protest. Maybe they attended a support group which involved a pronoun circle, or were required to give this information while introducing themselves at the beginning of a class in university.

I imagine that most people are introduced to queer theory by being confronted with some kind of terminology that they didn’t know the meaning of. And I imagine that most of them, like the majority of humans do when confronted with new concepts, asked what the word meant, or went home and did some research on the computer.

So, to sum up, the language of the community provokes curiosity. And the language is everywhere.

But the language of the community also demands participation, on some level, from people who don’t identify as transgender, and may not even be very knowledgeable about the concept what it means to be trans.

For example, I’m sure most of us are familiar with the notion that for trans people to be comfortable sharing their personal pronouns, we all have to share our pronouns, which involves deciding which ones we prefer. The idea here is that cis people don’t even think about it — they just go with whatever they’ve been told their pronouns are. But when you put that in their hands, when you make it a choice, of course they think about it. It sparks the train of thought: why shouldn’t I use my assigned pronouns? What do my assigned pronouns make people assume about me? If I used different pronouns, would people’s perception of me be more in line with who I really am?

The entire concept of being cisgender has a similar effect. Unlike being straight, white, or able-bodied, being ‘cis’ isn’t put forward as something people just “are” — it’s something people choose to be. Even when this isn’t overtly stated, it’s implied. How can someone know how they feel about gender if they, a cis person, have, by virtue of being cis, never really questioned their gender? And if a person actively questions their gender, for more than a couple of minutes, that in itself is a sign that they can’t be cis — because if you are cis, what is there to think about? If people identify as trans because their assigned gender doesn’t fit them, what does that say about cis people? That through some kind of coincidence, 99% of the time, people do happen to prefer the roles and social contracts assigned to them based on their genitals at birth? Or simply that they haven’t thought about it enough?

And of course, one element of queer theory is the dismantling of biological sex as a concept, and the complete inclusiveness within gendered institutions for trans people. Meaning things are being redefined, everywhere — famously, in some regions midwives have to adjust the terminology they use for all patients to refer to “chest-feeding” instead of “breastfeeding”, “mothers” as “parents” or even “carriers”, and on a national level even genders themselves are being redefined. Notably, the proposed Gender Recognition Act makes gender a kind of “opt-in, opt-out” experience for every single person in the country. So if you attend school, university, a support group, use the internet, identify as a feminist, have a baby, or exist in a country with something like the Gender Recognition Act, not only are you introduced to gender identity and queer theory, but you actively participate in it.

In general, the trans community demands that cis people be constantly aware and quite vocal about the fact that they are cisgender. Everyone must have a gender, everyone has to participate. I haven’t found other communities to act this way, in my own experience. As a lesbian, I don’t demand that straight people tell me they’re straight when I first meet them, or expect straight people to be more publicly affectionate with their partners so I could feel more comfortable holding my girlfriend’s hand. I’ve never met a religious person who demanded that I introduce myself as an atheist, either, or in fact that I call myself anything in particular, or do anything in particular, while respecting my status as a person outside of their faith.

To be clear, I am not saying that by simply using its own language, the trans community is forcibly indoctrinating anyone who happens to be around to hear it. What I am saying is that using obscure and confusing language, and even going as far as to apply this language to people who aren’t in the community which uses it, piques the curiosity of outsiders, especially the most compassionate, liberal outsiders who want to understand the politics of an oppressed minority like trans people, and so are driven to learn more about the origins and meanings of the terms that they have heard.

Step Two

Recruitment: Euphoria and Dysphoria

I would estimate that the majority of people who are curious about queer theory and trans politics leave their introductory phase with pretty basic knowledge. They might be familiar with the “born with the wrong body” narrative, or the more modern narrative of some people simply “identifying as” another gender, without any real insight as to what either of these experiences entail. They are probably familiar with trans women and trans men, and nonbinary people, but without an understanding of the dynamics between these three groups, or the notion that trans people of different genders are oppressed on different levels. It is probable that they haven’t met a trans person in real life. If they have, said trans person most likely described their experience of being trans very favourably, talking about finally being able to be themselves, being accepted by the world, coming into their own, and having a supportive community of peers. The trans person probably did not delve into sex dysphoria, suicidal feelings, or any particular negatives about life as a trans person.

A couple of years ago, the term “gender euphoria” sprung into existence in online communities. The idea of this term was to shift focus away from “dysphoria” — something not all trans people experience — to “euphoria”: something that is possible for all trans people to achieve. I recall reading about people who never felt any particular distaste for their assigned gender, and never had any problems with wanting to change their body, and would’ve happily lived as they were, but also simply preferred being the gender they identified as. It wasn’t that their assigned gender made them feel bad, but their chosen made them feel even better.

Meanwhile, dysphoria was pushed aside as a dated, if not offensive, experience to have. Trans people who continue to advocate for dysphoria being the cornerstone of transition and trans identity were, and still are, shunned in liberal circles, relentlessly mocked and called “scum” for taking this viewpoint. Trans people who experienced physical dysphoria are questioned on a more general level as well because, referring back to some of the inconsistencies I outlined in Part 3, conflating their sex characteristics with their gender identity is considered cissexist, and regressive. One cannot simply say, “I am a man, so I shouldn’t have breasts”. What does that say about trans men who still have breasts? Or trans women, who may not have breasts, and yet are not men? No matter how bad a person’s dysphoria is, there’s no right way to talk about it in relation to their trans identity. The only right way to talk about trans identity is when it focuses on gender, and feelings, and spirituality, and anything else vague and difficult to define. That way, there is no possible condition or trait that would rule out any given person from being transgender.

Because, to reiterate, is there any condition or trait that would rule out any given person from being transgender? If sex dysphoria is irrelevant, dissatisfaction with ones assigned gender is irrelevant, personality is irrelevant, and personal preferences in terms of clothing and physical appearance are irrelevant… what stops anyone, or in fact everyone, from potentially identifying as trans?

At this point, questioning people begin looking for clarity on what exactly sets trans people apart from other people. How does a person know if they are trans? What are the signs?

As it turns out, pretty much anything in the world can be a sign of being trans. Anything, from happening to have personality traits and hobbies which are traditionally associated with the opposite sex, from preferring to have sex in a certain way, to experiencing severe dissociation and impulses to self harm, to for no apparent reason deriving enjoyment from being called by certain pronouns, is indicative of being trans. The toys you played with as a child can be indicative of being trans. And if not that, how often you cry can be indicative of being trans. And if you try hard enough, you can find at least one, if not several of these traits, in literally every single person on earth.

In my opinion, this qualifies as the “mystical manipulation” element of how Lifton’s principles of mind control are applied to the transgender community. When we’re questioning or newly identifying as trans, we’re encouraged to start combing our life history and present circumstances for evidence that we were trans all along — even things which, rationally, could be easily explained by other factors. As an example, small children declaring a hatred of their genitals and longing for a different configuration is considered empirical evidence of innate transgenderism, when in reality children being overly knowledgeable about their own genitals and having self-harm impulses is actually indicative of sexual abuse. Similarly, adults feeling disconnected from their physical body and having a shaky sense of self are symptoms of PTSD — but if one’s gender is involved, despite any past trauma, the person is just trans. A person who wanted to remove a body part other than their genitals of secondary sex characteristics would be diagnosed with BIID, but if their target body part happens to be a sexed one, they’re just trans. And in general, a person who’s preoccupied with what their body looks like might have some kind of dysmorphic disorder, whether this compels them to change their features with surgery, or use steroids to achieve their unrealistically desired level of fitness — that is, unless their ideal body doesn’t align with societal standards of the ideal body for their sex, in which case, they’re just trans.

The trans community is not the only group which recruits new members using this process. Famously, the cult of Scientology offers free “personality tests” which always show results of the recruit being depressed, unfulfilled, and in other ways tragically flawed in ways that only the group can fix. And then, in the trans community, once someone has identified some traits within themselves which indicate trans-ness, they aren’t turned away by words like “dysphoria”, concepts like hating one’s body, hurting oneself, feelings like self-loathing and disgust and alienation. Instead, they find “euphoria” — loving one’s new body, successful surgeries, becoming the person they always wanted to become, feelings like contentment and self-admiration and solidarity. Transitioning is the panacea that can solve all of life’s problems — and if they don’t even have any problems, the trans community can at least offer endless validation and cheerleading for every minuscule life choice they make.

There’s no crime in being positive, but given the previously noted observations — that anyone can be trans, and that cis people are expected to actively participate in using the same framework of ‘gender identity’ that the trans community does — it is not a mystery to me why it’s so important that trans people are expected, at all times, to put their ‘best face forward’, and keep the less savoury elements of being trans hidden away from the general public.

Step Three

Fringe Membership: Identity

One does not simply identify as “trans”. For all I’ve been referring to “transgender identity” and the “trans community”, the word transgender is just an umbrella term which describes a general state of being but is not really an identity in itself. For the questioning individual who has started exploring queer theory, and who has identified some evidence in their personal history of present lifestyle that is indicative of being trans, the next step is to decide exactly which label fits their experience best. This act ends the questioning phase, and their tenuous, uncertain link to the transgender community becomes something that is now part of their everyday life and, in fact, a crucial element of their sense of self.

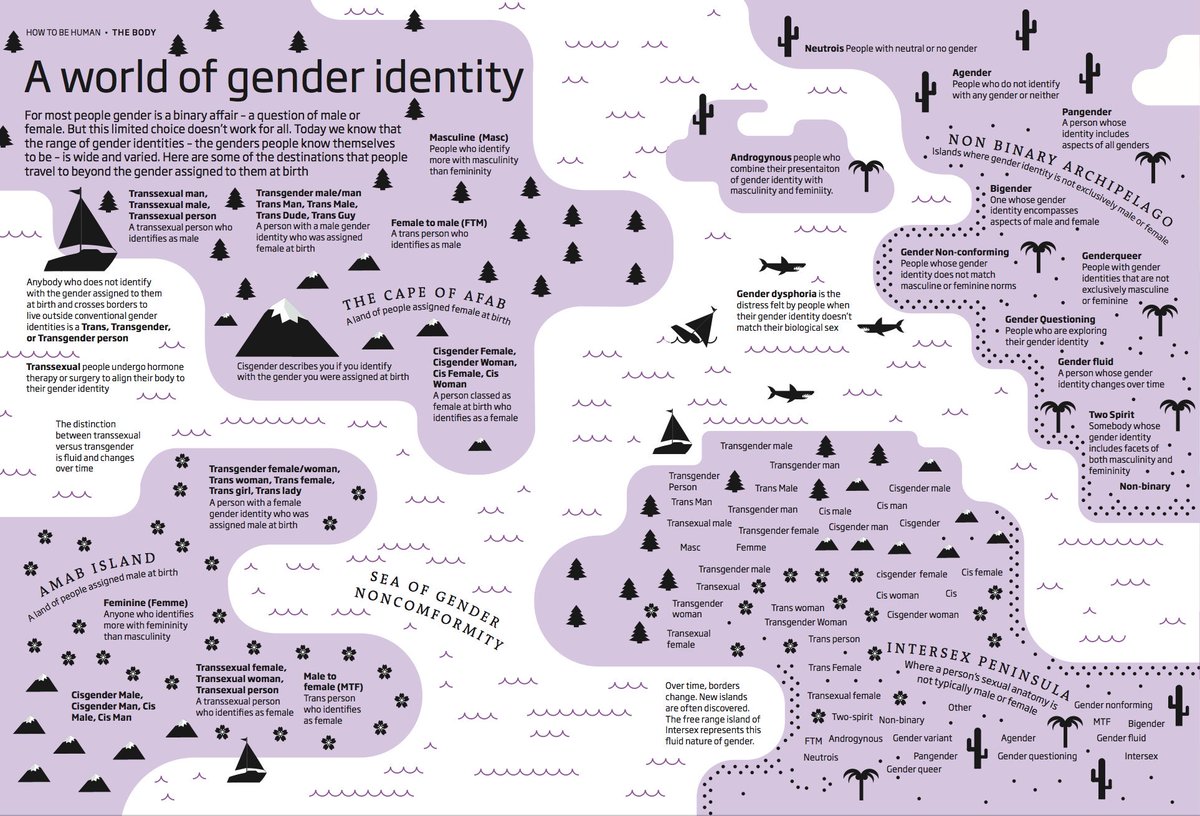

A mandatory condition for being able to stay in the trans community beyond the ‘questioning’ phase is examining yourself and adopting a specific gender identity from within a framework of already existing gender identities

Charts like this, and others along the same lines, share the same basic theme: one’s personal gender identity is based on their preference for ‘masculinity’ or ‘femininity’, and the degree to which they prefer one over the other. As much as most members of the trans community will hand-wave or deny this, masculinity and femininity are not simply aesthetics or personality traits but rigid social roles, both involving fixed sets of behaviour for whoever occupies them.

This, in my experience, means that when we enter the trans community and choose our label, our behaviour changes with it. Maybe a person who is masculine-leaning was always athletic and a natural leader, but in order to live up to his identity as a man or masculine person, feels the need to become more stoic and assertive. Maybe a person who is more feminine-leaning has always been physically weak and attentive to others, but in order to live up to her identity as a woman or feminine person, feels the need to display her emotions more often. And maybe a person who is agender becomes aware of acting too much like either sex, and is constantly trying to strike a balance between being emotional and stoical, strong and weak, boisterous and refined, to avoid any miscommunication about what their gender identity is.

Gradually, we begin to change. Elements of our personality which don’t fit out gender identity become discarded, one at a time. We adjust the way we walk, and talk, the way we style our hair, the way we dress. We become well-versed in trans-related political issues, we make new friends, and perhaps leave behind old ones. And as being trans becomes a larger and larger part of our self-concept, we start looking into ways to make sure that our lifestyle is still viable in the long run.

Step 4

Full Membership: Commitment

When we talk about manipulative groups, there is a pretty consistent hierarchy across all of them. The bottom rung of a manipulative group is occupied by what we call fringe members — people who run in the group’s circles without having made any real commitment to it. If someone is going to walk away from a group, it will most likely happen during the transition from fringe to full membership, when the individual is expected to give up some element of their own life — usually, something that keeps them tied to the outside world. As we discussed in Part 2’s explanation of ‘milieu control’, this ensures that the individual will have a far more difficult time leaving the group, because they will have given up so much of their old life that there will be next to nothing to go back to.

This journey from fringe to full membership is what caused me to falter in my trans identification. This is also where we draw the line between ‘reidentified’ and ‘detransitioned’ people. I spent most, if not all, of my life never feeling like a girl or a woman, and identifying away from those terms the moment I had the language to do so. But I never told my family about my dysphoria or trans identity, I never took a pill or got a shot, and I never made any surgical changes to my body.

This doesn’t mean I wasn’t committed, on an emotional level, to the transgender community or my personal identity as a trans person. I was certain that I would get surgery and change my legal name and sex — in fact, I thought I would die if I didn’t do all of those things as soon as possible. I was completely prepared to change my body, to throw away my relationships with any critical family and friends, and even move to an entirely new country if that was what it took to successfully transition and achieve happiness. But in reality, I didn’t get around to doing any of those things. That made walking away, for me, a thousand times easier than people who, for example, had made physical and legal changes, lived socially as their chosen gender, participated in the local LGBT community, and may even have been stealth before they detransitioned.

That is, at it’s core, the difference between fringe and full membership status of a manipulative group. How much a person has sacrificed to be a part of a group is directly proportional to how long they will stay in the group. And really, what we sacrifice to a manipulative group is not just in the material loss. It’s not about the money, the job, the house, the friends and family, the body part. What we really sacrifice is our ability to go back to the way things were before.

Step 5

Cult Membership: Lifestyle

How do we tell the difference between a manipulative group and a cult?

I’ve already mentioned the fringe and full membership levels of the hierarchy, but in a manipulative group, there’s one more: the “inner circle”. These are the people who make the rules — or, in a large enough group, are at least considered important that their opinions on what the rules should be override the opinions of everyone else. The inner circle is who we defer to when we’re unsure what to believe.

The inner circles of manipulative groups is a difficult topic to research, so this is purely speculation, but in my personal experience the “inner circle” is populated entirely by narcissists and sociopaths who understand, on some level, that the ideology of the group is baseless and really only functions as a means to control its members. If someone lacks inherent narcissism or sociopathy, they flounder forever within the fringe or full membership categories. In my view, this is how a manipulative group is able to continue operating after it’s original inner circle has left or died. One narcissist or sociopath, in terms of behaviour and motivation, is extremely similar to any other given person with the same disorder. Thus, the operation of the group will continue to be extremely similar as well, so long as the inner circle is still composed narcissists and sociopaths.

Unlike a manipulative group, the cult has yet another category after this: the “leader”. In a cult, a single leader controls the inner circle, but in a manipulative group, the inner circle is relatively autonomous. The example I like to use is that the Christian church, a massive organization which attempts to control the behaviour of its members through fear and shame and which very obviously applies all eight of Lifton’s criteria in its methods, could be considered a manipulative group. However, a single Christian congregation, which has one reigning authority figure and also meets all of this criteria, is not only a manipulative group, but also has the potential to be a full-blown cult.

If it was not clear by now, I am not saying that by virtue of being a manipulative group, the trans community is also a cult. In my view, unless the trans community somehow acquired a singular “leader”, it could not possibly meet the criteria for being a cult. What I am saying, however, is this: the intense manipulation of thoughts and behaviour within the trans community, the way that trans people are made to feel guilty and ashamed for imagined shortcomings, the nonsensical ideology that trans people are expected to unquestioningly believe, and the undercurrent of excusing, ignoring and denying crimes committed by certain members of the group — all of these elements of the trans community function as a way of grooming members of the transgender community to be recruited into small, cultic groups locally, of which the “leader” is one narcissistic or sociopathic trans person, orbited by other trans people who have been successfully trained, after years of manipulation, to cater to narcissists and sociopaths.

A bold claim, I know. So let’s back up and talk about this final stage of identifying as transgender.

At this stage, every element of someone’s life has impacted in some way by their gender identity. In the previous stage, their body, legal status, and social circle changed. Maybe it ends there, or maybe it doesn’t. Maybe they quit their job to do full-time activism. Maybe they are in a relationship with another trans person. Maybe they aren’t as close with their family as they used to be, or maybe they aren’t even on speaking terms with them anymore.

In my experience, the message people receive that this stage of transition is that any sense of isolation can be healed by more interaction with their trans peers. They should mentor a younger trans person, or volunteer with other trans people. If they’re having issues at home, they should move in with a trans roommate. This not only fosters a sense of dependence on the group as a whole, but increases the chance that any given trans person will eventually bump into one of the cultic groups described above. If the person has not already made contact with one of these narcissistic or sociopathic “leader” figures, they will now. And with nothing left to lose, it will be much, much harder for them to extricate themselves from this person than it might have been if they were in a different stage of their lives.

At this time, the group member will also be struggling with a number of induced phobias. Phobia-inducing is a manipulation technique that I have mentioned briefly a couple of times throughout this essay, and I think that in general, all transgender people who have made it to this stage of group membership have the same general list of induced phobias.

For example — and I mean no cruelty or judgement in pointing this out — a trans person at this level of group membership is terrified of being misgendered. Why? Because trans ideology dictates that our reality is dictated by how other people see us, and also that our sense of personhood is inextricably tied to our gender identity. So, when someone wilfully or accidentally uses the wrong name or pronoun for us, we feel like it goes far beyond the pronoun, and beyond even our gender identity — our personhood, our humanity is being actively denied by this person. We don’t know how to cope. Under trans ideology, misgendering is a violent act — we feel assaulted. Under trans ideology, calling someone by their birth name is ‘deadnaming’ — we feel misunderstood. Under trans ideology, even accidentally misgendering a person means that deep down inside, the person still thinks of the trans individual as the gender they were assigned — we feel deceived, and lied to.

But how would we feel if we hadn’t been exposed to any of these ideas? If we think back to before we transitioned, did our original name and pronouns really offend us that much? Even if we prickled when someone said ‘she’, or never felt that our birth name fit us properly, did we feel such pain and outrage back then? Why did things change? Why, after going through the process of accepting ourselves and finding people who can understand us and even physically changing our bodies to reflect who we are, do we feel worse than we originally did when it comes to other people not being on the same page as we are about our gender? What made us feel so insecure?

The fear of misgendering controls us. It makes us hesitate when we meet new people: we’re afraid of the assumptions they’ll make about us, we’re afraid that they’ll see us differently than we see ourselves. It makes us vulnerable to being wounded and hurt by the outside world, which is populated by people who don’t understand how to address people who are trans, even when they mean well. And we withdraw. All because of a fear of rejection that was instilled in us by other people.

Misgendering is just an example, though. In my view, the most dangerous and salient induced phobia that can be found at this stage, and the most intertwined with cult membership, is this:

Trans people who were assigned female at birth have had instilled in them a debilitating, overwhelming fear of trans women’s disapproval.

And if you’re reading this and rolling your eyes, and thinking to yourself that this is normal: it’s not. It is absolutely not normal to experience fear in response to the thought of someone disapproving of you.

And I will be honest: there have been several parts of this essay where I have made a point of making statements which are objectively innocuous, but which I know will induce a sense of discomfort, panic, and fear in my intended readers (that is, trans people who were assigned female at birth). This is because I know that the most salient, most intense, most terrifying fear we experience as members of the trans community is the fear of backlash: the fear that if someone finds out what we’re reading, doing, thinking, or feeling, a punishment will be handed down to us, probably in the form of public exposure followed by complete excommunication. If someone were to create a little window into our minds, we would lose everything.

And now I’m begging you to ask yourself: who is making you feel like this?

Whose wrath are you afraid of, really? Whose disapproval has the potential to destroy your life? And if you’re thinking that your other friends who were assigned female at birth would be the agents of this destruction, by calling you out and cutting you off, think about it: would they be more motivated by the idea of punishing you, or protecting themselves from punishment? And in that case, who would punish them? Who is sitting at the top of the pyramid, handing down all of these threats without having anything to fear themselves?

Can you imagine a trans person who was assigned male at birth experiencing this fear like you do? The fear of backlash? What would they have to do, honestly, to earn the kind of response you’d get if you admitted to simply reading an essay? Can you think of anything?

My point is this: if everything has gone according to plan, an afab trans person at this stage of identification should be completely at the mercy of trans women. Their biggest fear, the worst thing they can possibly imagine, is disapproval: saying or doing the wrong thing, being “exposed”, and ending up excommunicated. They have a sense that inside of them is a some kind of evil that will eventually show itself, and someone will notice, and they will be punished. They are constantly on thin ice. They could be next. That’s how it feels.

That’s how being in a cult feels.

Conclusion

If you find yourself relating to what I have said, I cannot reiterate enough that things don’t have to be this way.

Let me be as clear and transparent as I possibly can: I am not saying that you have to change or reevaluate your gender identity. I am not saying that you have to detransition. I am not about to try to sell you on some other ideology, or claim that I’m the authority on how to achieve freedom of thought.

But I am going to ask one thing of you. And it is completely optional. But I’m still going to ask.

Take the thought experiment I put forward in Part 3, and make it a reality. For twenty-four hours of your life, make a point of thinking about whatever you want. You don’t have to say anything or go public about it — in fact I think it’s probably better that you don’t — but for just one day, make your mind completely your own. Sit with this essay and decide for yourself which parts, if any, you think were valid and reasonable and which parts you think were total nonsense. Think up some rebuttals if you want. Or don’t think about the essay at all. Prioritise what you want to prioritise. And if you catch yourself thinking that you shouldn’t have a certain thought, that you’re not allowed, that you’d be in serious trouble if somebody knew what was going on inside your head, maybe take a moment to read over the affirmations that I myself used so often when I was learning how to think for myself again.

First, I know who I am. Other people’s opinions about me does not change who I know myself to be.

Second, I know what I believe. I can read and consider the opinions of others without giving them control over me.

Third, I am entitled to privacy. I can be judged by my words and my actions, but nobody can judge me for my thoughts.

Last, thoughts are not dangerous. I can hurt others with my words and my actions, but nobody can be harmed by my thoughts.

If you’ve read this far, I want to sincerely thank you for listening to what I have to say. Please feel free to leave feedback in the comments section, or to send me an email at newthoughtcrime@protonmail.com. I’ll try to be as responsive as I can.

“Unlike being straight, white, or able-bodied, being ‘cis’ isn’t put forward as something people just ‘are’ — it’s something people choose to be.”

I disagree. I’ve overwhelmingly heard the opposite, that cis is something people innately are. And I actually think your nearby claims about the rhetoric – that pronouns/presentation/etc are something cis people innately don’t have to worry about – contradicts the bit I quoted. I think the logic goes more like this:

Cis people are people whose assigned gender (presentation, behavior norms, name, body, pronouns and all) totally work for them, without them ever questioning it.

Cis people are innately, permanently cis, just like trans people are innately, permanently trans, white people are white, straight people are straight, etc.

If you’ve ever felt discomfort with or even questioned your assigned gender characteristics, you’re probably innately, permanently trans, because cis people never have to think about it.

…

LikeLike

Hey, thank you for your comment! I think this is an example of what’s said or claimed within certain parts of the trans community being different than what’s implied. When I was a teenager involved in the trans community, the message went along the lines that some women, for example, are cis, innately, inherently… but also, that being a woman involved being passive, weak, feminine, submissive, selfless, and conforming to this impossible, idealized standard of womanhood that doesn’t come naturally to anyone. To be a woman, I had to “feel” like a woman — and of course, nobody could tell me what this “feeling” was like, and of course, I didn’t experience it, because I just “felt” like a person. I got the message loud and clear that an afab person like me who didn’t experience this calling towards stereotypical womanhood was not a woman at all, and that if this vision of my future didn’t appeal to me, I had some soul searching to do. So I totally get where you’re coming from here: the innately cis person is definitely put forward as a real thing, but in a way that doesn’t realistically apply to anyone, or at least not anyone who becomes invested in queer theory to the point where they believe that gender = personality, because inevitably, it is impossible for anyone’s (and especially any afab person’s) personality to actually align with what the female gender is presented as.

LikeLike

I also felt a little disappointed by your lack of support for the idea in the final paragraphs of part 5 that trans women are the ones running the manipulative group/mini cults you describe and that amab trans people generally have more autonomy/power in those spaces. I am afab but not really a part of the trans community, so I know I am not your target audience, but since the rest of your piece was so accessible (& easy to apply my own reasoning to given how carefully you cited the sources of your data claims/the frameworks for your analysis) I wish you had provided more explanation or external support for that pretty bold claim.

I’ve definitely seen amab trans people be excommunicated for diverting ideologically (the recent dragging of ContraPoints on Twitter comes to mind) and I think it would be easy for people entrenched in the rhetoric you describe to simply accuse you of being terfy (for suggesting that trans women persist in behaving like and/or enjoying privileges typical to men) there and dismiss you.

I appreciated this piece in general. A lot of it was very affirming/illuminating.

LikeLike

This is a great critique and I really appreciate it. To be honest, with this part of the essay I’m relying on my claim ringing true to afab people’s personal experience. When it comes to afab people who’ve been in and around the trans community, I feel like we’ve all been in or witnessed a group like the one I was describing. Other than that, I’m not sure how to find any data or evidence to support what I think is going on, but I’ll be taking this to heart and brainstorming other ways to put my point across.

I think the situation with people like ContraPoints is actually pretty standard for a cultic group dynamic, because someone like Contra is given the privilege of being “innocent until proven guilty”. For afab people in the trans community, everyone carries this burden of having to constanty meet a standard of purity, of literally maintaining correct behaviours /and thoughts/ at all times, /earning/ their place as a “good person”. An amab trans person is presumed to already possess this “purity” until they do something extreme. And even then, is the backlash against Contra as bad as it would be for an afab person who’d done and said the same things as her?

Thank you again for commenting. I’m glad you enjoyed the essay overall. 🙂

LikeLike

I’ll echo what was said above (I realize I’m years late) and say that my own decade in the trans community in my country doesn’t really reveal MTFs as the centre of it all. I witnessed FTMs deferr to trans women in the earlier 2010s less out of a fear of transmisogyny accusations and more because we tend to be socialized to be meeker and agreeable, while they generally aren’t. Most of the social terrorism I’ve experienced comes from non-transitioning female-presenting AFABs who claim to be trans or some flavour of NB. The inherent disdain for men in these predominantly feminist circles (I may be a bit older than you and saw this movement spring up and out of university women’s studies programs in the late 2000s) drives many of these people to squeamishness around MTFs in person, who have generally stuck out badly and integrated socially quite poorly into circles populated by women and various AFABs.

Also, if you’ve kept up with AMAB detrans people Limpida writes brilliantly about how the loathing for men and the constant mockery directed towards them in progressive circles drove him and other young men who didn’t relate to being loud or aggressive to feel they might be trans. I know plenty of AFABs who are completely sadistic narcissists, and plenty of AMABs who are incredibly socially isolated and vulnerable. Loads of narcissistic AMABs too, but I see females bounce back from group ejection more robustly than males, whose social isolation is only compounded by the greater pressure towards gender role conformity males tend to experience. This may be changing as being MTF becomes a greater and greater sacred cow, but I want to share my experience to contrast with yours, as personally you really lost me when you put the burden on natal males. I’ve seen sociopathic cis women at the centre of personal abuse rings within the queer community where FTMs are targeted because we’re vulnerable to being manipulated on the grounds of fearing our “male privilege”.

Personally I think it would be more effective to broaden the scope of this observation unless you have strong evidence to the contrary. Otherwise this has been a fantastic series and my own experience of being duped into making irreversible changes to my body that have given me none of the sense of peace or wholeness that was promised. I have also seen plenty of predatory and socially vile behaviour from MTFs so this isn’t about coming to their defense as much as it is observing that this regime tends to prioritize those identifying or presenting as women, as tolerance for insubordination seems to be much lower when the person doing it has “privilege” (which of course identifying as female even if nothing else changes negates, naturally lol).

LikeLike